|

|

|

The Origins and Early History

There are many legends relating to the foundation of Minsk and the origin of its name. Situated on the watershed of the river-routes linking the Baltic to the Black Sea, its trading history going back to prehistoric times, some have thought that city owes its name to the word miena or "barter". Others look to a hill-fort known as Haradyscy by Strocyce, a "Skansen"-village a few kilometres to the west of the city on the banks of the river Menka, which flows into the river Ptyc, and on to join the Prypiac and Dniapro. A heroic folk-legend has it that a giant called Menesk or Mine kept a mill, by the banks of a river, and ground rocks and stones to make flour for bread, in order to feed the war-band he had assembled to protect his settlement, and safeguard its prosperity. This depended, no doubt, on the portage of goods between the headwaters of the Prypiat, Dniapro and Nioman. So Menesk - later Mensk -came into being. The reference to "stone-flour' may allude to the kneading and baking of potters clay used in the brick-making and ceramics industry, which from the earliest times flourished in the area. There was no lack of wood to fire the kilns.

In prehistoric times the 'domain of the bear' predominated over the 'domain of the goose'(as Napoleon's soldiers aptly dubbed the forest- and meadow-lands of this area), with vast and impenetrable primaeval forests covering most of the country, and serving as a Delphic 'wooden wall' to its successive inhabitants against attacks from the East. Scattered Lithuanians and Jatvyhs hunted and gathered, until merged with the more advanced Slavonic farming tribes, moving northwards from the Carpathians during the so-called Dark Ages. These settled the area forming the watershed of the rivers flowing to the Baltic and the Black Sea, where the early Belarusans founded prosperous townships at Polacak, Viciebsk. Smalensk, Minsk and Horadnia. Of these Polacak, first mentioned in the chronicles for 862, was to became the most important.

During the era of Viking expansion along the East European waterways, many towns and principalities were ruled over by Scandinavian warlords; in the 9th century the lands of Polacak were raided by two Viking princes Askold and Dir, and by the last quarter of the 10th century a Prince Rohvalad (Norse: Ragnvald) reigned over the Belarusan principality of which early Minsk formed part. The Belarusan nobility to this day distinguishes between families of old Lithuanian and those of Scandinavian descent {Hedyminoviiy and Rurikovi&y).

Minsk and the Principality ofPoIacak (989 - 1249)

Rohvalad's daughter Rahnieda (Norse. Ragnheid) was baptised;

she became the wife of Prince Volodymir (Norse: Valdemar) of Kiev, and bore him a son Iziaslau. Volodymir was baptised a Christian by missionaries from Constantinople in 988; the population of Polacak accepted Christianity in 989, and by 992 the city had its own Bishop. On the death of Volodymir, Iziaslau became Prince of Polacak, and his half-brother Jaraslav - Volodymir's son by a previous marriage - became Prince of Novgorod and later of Kiev. Other sons acquired his domains among the Finno-Ugric tribes of what was to become Muscovy. "Since that time, as the chronicler recorded, the grandchildren of Rohvalad raised the sword against the grandchildren of Jaroslav". From the outset there was little unity betwen the warring Princes of "Rus". Isiaslau (d. 1001) of Polacak, the son of Rogvalad was succeeded by his son Bracaslau, who in turn was followed by his son Usiaslau the Er hanter (1044-1101).

The dynastic rivalry between the two houses of Kiev and Polacak explains the turbulent history of Minsk in its early years, situate as it was on the southern borders of the latter principality. The centre of the town had shifted to a new site, giving access to the headwaters of the Vilja and the Biarazina, at the confluence of the Niamiha and Svislac rivers. Here also the steep banks of the Niamiha, the high ground south of the stream and Trinity Golden hill offered a good defensive position. Public buildings, dwelling houses and fortifications were raised of timber The first recorded mention of Minsk in 1066 however relates to the dynastic wars with Kiev. After Usiaslau of Polacak had raided Novgorod, and brought back to his capital the bells of the Cathedral of St. Sophia, to hang them in his own Cathedral of that name, the three sons of Jaroslav in retribution attacked the city of Minsk: "The people of Menesk (Minsk) barricaded themselves in the town, but the three brothers, took Menesk and killed the men, carried off the women and children into captivity, and went towards the Niamiha".

Treacherously seized whilst attending a parley in Smalensk with Isiaslau and the princes of Kiev in 1067, Usiaslau and his two sons were held captive in Kiev, until an uprising of the inhabitants set them free. Prince Isiaslau fled to Poland, and the Prince of Polacak was offered the throne of Kiev in his stead. The story goes that Usiaslau longed to return home, and declined the honour for the love of his native land: " He was, as the chronicler records, called back to Polacak by the pealing bells of St.Sophia.The first uncensored Belarusan historical opera to be performed in Minsk, Usiaslau the Enchanter, Prince of PoIacak (1944) by the composer M. Kulikovic, dealt with this romantic theme. The bells of St. Sophia were to become for Belarusan exiles the symbol of the call of the homeland.

One of the remainig castle buildings.

Usiaslau's principality ofPolacak was, on his death, divided between his sons: the fiefdom of Minsk fell to Hleb, who thus became the first sovereign prince of the city. Internecine quarrels weakened the northern principalities, and encouraged the Kievans to reopen hostilities. In 1104 they ravaged the principality of Minsk, and shortly thereafter the warlike Lithuanians moved in from the west. Vladimir Monomach again besieged and took Minsk in 1116. Three years later in 1119, in a further campaign against Polacak, after a battle on the banks of the Biarazina, the Kievans "attacked the town, and left neither man nor beast in it." Prince Hleb Usiaslavic, together with his two sons Rascislau and Valadar, was taken into captivity, where he died in exile later that year. He was succeeded as Prince of Minsk by his son Rascislau, but yet again the Kievans attacked in 1129, and placed their nominee Isiaslaii Mscislavic on the throne, dispatching Hieb's children to serve the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople. However the principality reverted to the princes of Polacak in 1146, with the return of the two sons of Hleb, Rascislau and after him Valadar(1151-1158), though Syrakomla gives different dates, and the chronicles for this period are incomplete. On the death of the latter prince, Minsk is thought to have been governed by Valadar's son Prince Vasylka, at least until 1195. During the reign of the Grand Duke Mindaiih (c. 1200-1263)

of Lithuania, Polacak entered into an alliance with him to expel the Baltic Germans, who had invaded the principality. Thereafter it appears to have become a Lithuanian apanage, for by 1220 the overlord of Minsk was Prince Erdzivil, a nephew ofMindauh. Minsk continued as a semi-independent principality allied with Lithuania, for as late as l3l6 the records mention a Prince Todar Sviataslavic of Minsk as a witness to a Treaty between the Grand Duke Hedymin (d.1341) and the city-state of Novgorod.

The fall of Kiev to the Mongols in 1240 during the great invasion ofBatu Khan, the submission ofJaroslav, Grand Duke of Moscow to the Tatars in 1243 and the Lithuanian victory over the Asian invaders first at Kojdanava (1241) under Prince Skirmunt and then at Kruta Hora (1249) a few miles from Minsk, served to consolidate the union between the Belarusan principalities and the Grand Duchy. In 1252 Mindaiih and his leading nobles were baptised, and the Grand Duke was crowned with the approval of Pope Innocent IV in 1253. He fixed his capital in the Belarusan city ofNavahradak, some 100 km to the west of Minsk.

The Early Years of the Grand Duchy (1250 - 1499)

Little is known of the history of the city under the early Grand Dukes VaJselak (d. 1269), Trojdzen (1271-1282), and Lutaver (1282-1295) In 1323. during the reign of Hedymin (1316-1341), the capital of the Grand Duchy was moved from Navahradak to Vilnia.

The fact that Prince Jaunut Hedyminavic received from the Grand Duke Kejstut the principality ofZaslaue, and reigned in Minsk in 1345, where he was succeeded his son Michal, suggests that the city was by then a royal suzerainty Prince Michal was present at the coronation in 1386 of Grand Duke Jahajla as King of Poland in Krakow, and gave his oath of allegiance "for himself and his own" In 1390 Jahajla endowed a Catholic Church in Minsk, dedicated to the Holy Trinity and the Assumption of Our Lady. perhaps in part performance of his written bond on his marriage in 1389 to Queen Jadvyha of Poland, to establish Latin-rite Catholicism in his domains, its site in the city is not known, and the wooden building is reputed to have been destroyed by fire in 1409. Many of the suzerains of Russian principalities to the east ofSmalensk, anxious for protection against Moscow - now reduced to the state of a Tatar satrapy. - sought alliance or union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, so that soon the Grand Duke Alhierd (1345-1377) acquired Ihc (itie of Rex Litvinorum Ruthenoruirnfiic. with domains stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

Union did not imply subservience however; and it is noted by Syrakomla that the banner of Minsk was not among the united army of Lithuanians, Belarusansand Poles, who under Grand Duke Vitaut(1392-1430) defeated the Teutonic Order at the Battle of Gruenwald in 1410. The city had sided with Prince Svidrigajla in a dynastic dispute against Grand Duke Hedymin, and Prince Urustaj of Minsk appeared in 140S, as a witness to a Treaty of mutual aid signed between Svidrigajla and the Grand Duke Basil of Moscow. The establishment of Minsk as a Namiesnictva (Royal Shire) in 1413 coincides with the absence, noted by Syrakomla, of the city's seal from the Charter of Horadia in that year, - though few other noblemen . ." the Greek-rite were present at that conference. Thereafter the city appears to have been governed by a namiesnik or Sheriff representing the Grand Ducal authority as hereditary Prince of Zaslaue. This might indicate that Minsk had declined in importance since the Mongol invasions, the sack of Kiev, and the growing threat to Black Sea trade from the advancing Turks. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the subjection of the Crimean Tatars to Ottoman rule in 1475, were to have far reaching effects on the economic, political and religious life of Minsk, and indeed of the whole Grand Duchy.

Renaissance Minsk (1499 - 1569)

In 1499 Grand Duke Alexander Jahajlavic granted to the city of Minsk a specially favoured autonomous status known as the Magdeburg privilege, manifestly to stimulate trade. This weak and vacillating monarch, in an attempt to pacify his increasingly aggressive Eastern neighbour, the self-proclaimed Tsar Ivan III of Moscow, sought the hand of his daughter the Grand Duchess Helen, whose mother was Sophia Paleologos, a relative of the last Byzantine Emperor. Alexander unwisely signed a marriage contract fraught with opportunities for Muscovite interference in Lithuanian religious affairs and matters of state. Urged on by her Muscovite chaplains, Helen pressed the candidature of her confessor Jonas, Archimandrite of the Ascension monastery in Minsk, to be appointed Metropolitan of Kiev in 1502 This simple but inflexible man, was to be the first Lithuanian Metropolitan since 1439 unwilling to support the Florentine Union, entered into between the Latin and Greek Churches in the face of the Muslim Turkish threat. The highly critical historian Vakar observed that, until the appointment of Jonas, the Catholics and Orthodox maintained quite friendly relations in Belarus: "The Orthodox clergy in the Grand Duchy took a sympathetic attitude towards the Union of Florence (1439), and would not have rejected it, save for the direct pressure of Moscow". Therein lay the root of religious discord in the country over the next five centuries.

The visit to Minsk in 1502 of the Grand Duke Alexander and the Grand Duchess Helen did little to avert a succession of disasters. The Eastern principalities of the Grand Duchy were progressively lost to Moscow. Minsk was beseiged by the Muscovites, relieved by Prince Hlinski and again sacked, (with the exception of the castle) by the Crimean Tatar Khan, Machmet-Girej (1506). The key Eastern fortress ofSmalenskwas taken by Tsar Basil III (1513), scarcely before the Grand Duchess Helen of Lithuania, his sister, was cold in her coffin. Fortunately by his victory over the Russians at Orsa in 1514, the Hetman of the Grand Duchy, Prince Constantine Astrozski, saved the city from further immediate misfortune. Prior to the battle, the Grand Duke Zyhimunt II {Pol. I.) and the whole Court came from Vilnia to Minsk to direct the campaign, in which the Namiesnik (sheriff) of the city. Prince Bahdan Zaslauski also took part. However, whilst Zyhimunt was away fighting the Teutonic knights in Prussia, the Muscovites in 1519 once again returned to ravage Lahojsk, Minsk, Hajna, Radaskavicy, Barysau and other towns, despite the stout resistance put up by Mikalaj Radzivil, Albrecht Hastold and the then sheriff of Minsk, Michal Zaslauski. Both Hastold and Radzivil attended the Vienna Congress of 1515 to set up a coalition against the Turks, and their banners were depicted by Skaryna in his allegorical engraving of the March ofthe Twelve Tubes (l5\9), as examples of "worthy princes and commanders to protect us from the hand of the heathen". Evidence of the impoverishment of the city is to be found in the military levies for 1529 fixing at 1,500 kop brosaj{he contribution from Vilnia. 300 from Kouna, Mahilou: 200, Biariescie: 150, whilst Minsk was only required to underwrite 50 kop.

The sorry decline of the traditional Greek- and Latin-rite churches in Belarus, both of which had become corrupt and refused to adopt the Belarusan vernacular, coupled with the failure of attempts to renew the Florentine Union, to consolidate a national church in the face of Muscovite intrigues and the continuing Turkish threat, led many of the most eminent noblemen and soldiers of the age - Radzivil, Sapieha, Kiska, Chadkievic, Pac and others, as well as some of the ablest writers and thinkers of the day, such as Vasil Ciapynski (1530-1603), Symon Budny (1530-1593) and the engaging diarist Todar Eulaseuski (1546-1616) -to embrace the Calvinistic reformed faith. For the less reputable, it was a convenient means of revoking Church endowments secured by their forebears on family estates, the churches now being divided. Some of the finest Belarusan church architecture of the period in the Byzantino-Gothic style is to be found in the evangelical churches at Zaslaue (1590), Dzieraunaja (1590), Novy Svierzan (c.1550), all near Minsk, and Smarhoni (1554) amongst many others. The development of a peculiarly Belarusan art-form in music - the kantycka or hymn, was also largely a product of the Reformation. It was the exodus of the nobles and burghers to Calvinism, rather than any schemings of the Jesuits (who in any case were not then established in Minsk), which resulted in the dereliction of the 13 Greek-rite churches, which according to the local historian Spileuski (1853) had flourished in Minsk at the close of the Middle Ages, including the ancient monastery of the Ascension. Moreover in 1547 the city was once again devastated by fire, which destroyed the Castle and a number of the churches in the Lower Town. As a result, in the latter part of the 16th century the Upper Town was laid out with broader streets and a greater recourse to brickwork in the reconstruction of the city. There were no stone or brick ramparts, the rivers Svislac and Niamiha served as moats to the east and north, whilst to the south and west the main defence was made up of semi-circular earth-works. In the light of the growing threat from the East, the stockade and redoubt in Trinity suburb were strengthened. The defence of the inhabitants of Minsk, however, depended chiefly on the superior fire-power of their artillery, the dense forests to the East, and an embargo by the Catholic European powers on the sale of fire-arms to the troublesome Muscovites.

Minsk under the Commonwealth (1569 - 1648)

There can be little doubt that the Council of the Stoglav (1551) in Moscow, proclaiming the supremacy of Russian Orthodoxy over all other forms of the Greck-ritc faith, the invasion of Belarus by Ivan IV ("The Terrible"), the subsequent capture and destruction of Polacak (1563-1579) by the Russians, the establishment in 15S9 of a Patriarchate of Moscow as the "Third Rome", and the breaking after 155S of Ihc embargo on arms for Muscovy by Protestant England and Holland, were four events so fraught with danger for the Grand Duchy, (hat it had virtually no choice other than to seek political Union with the Kingdom of Poland at Lublin in 1569, and renewed ecclesiastical Union with Rome at Bicrascic in 1596

One of many Greek-rite clerics conscious of the danger was Michael Rahoza. In 1576 he was appointed Archimandrite of the Ascension mon-astery in Minsk, which had remained vacant for several decades. He was consecrated Metropolitan of Kiev in 1588 by the visiting Patriarch Jeremiah of Constantinople who, "being unable to meet the financial demands of the Turks, had come to the North to look for money" (Guepin). Two years previously, the Patriarch ofAntioch, Joachim had returned to his Turkish overlords, "carrying off large sums of money" collected from pious Orthodox believers in Belarus and Ukraine, which in turn helped the Turks finance their campaigns against the Grand Duchy. The Greek Catholic (Uniate) Archbishop of Polacak, Josaphat Kuncevic, in 1622 stressed this peril in his reply to Chancellor Leu Sapieha's famous letter, reproaching him with his hostility to the Constantinopolitan faction, the non-Uniate Cossacks of Ukraine and their then covert supporters, the Turks: "Are we to allow the Patriarch, a Metropolitan, a bishop, nay, even a pasha who has taken the precaution of donning a monks habit and assuming the title of Exarch, to come to this land with janissaries, on the pretext of a pastoral visitation, in order to spy and hatch treasonable plots ? Are we not to prevent them because this would indispose the Cossacks?". Minsk was to play an important part in the struggle for the restoration of the Florentine Union, as the only effective means of ending the pretensions both of the Tsar and Patriarch of Moscow, and of Constantinople, to political and ecclesiastical supremacy over "all the Russias and all the countries of the North". A council of the clergy of the Greek Church was held in Minsk in 1620 presided over by Metropolitan Rutski with a view to obtaining adherence of the passive majority to the Union. The session, according to Syrakomla, appears to have been stormy, as a result of the bold intervention of the conservative, anti-Union monk, Todar Jarmolic. However, as the French church historian Guepin observed, "The extinction of the Ruthenian schism had become a matter of State".

The political union with Poland in 1569, and the problems involved in selecting a joint ruler for the Kingdom and the Grand Duchy, resulted in some curious situations, as where a reluctant French Prince, Henri de Valois, brought back from Paris as ephemeral sovereign in 1574, by a delegation including Chancellor Radzivil, began appending his signature and seal as Grand Duke to Decrees written in the old Belarusan language. The union also altered the status of Minsk, which became instead of a Grand-Ducal Nannesnitcva (Shire), a standard Vajavodstva (County) of the Reiypaspalitaja (Commonwealth), with Hauryla Harnastaj as its first Vajavod(High Constable), Mikola Talvas as Castellan and Bazyl TySkievic as Starosta (Lord Lieutenant). Minsk became not only the seat of its own County Court and Land Tribunal, but also after 1581 a session town in which the High Court of the Grand Duchy would sit when on circuit, a privilege it shared with Vilnia, and the former capital Navahradak. An occasional pleader in the Minsk Courts was Todar Jeulaseuski, who in his diary mentions his appearances at the Sessions there in 1583. During the wars against Ivan the Terrible (1563-1579), Minsk once again served as operational headquarters for the Grand Ducal armies, and the King and Grand Duke Zyhimunt Auhust III (Pol. II) sojourned there during the campaigns of 1563 and 1568. His successor Zyhimunt IV (Pol. Ill) confirmed the city in its privileges, granted the merchants the right to hold two Fairs each year and endowed the municipality with additional lands in 1592.

This was not always appreciated by the local population, stirred up by false rumours of impending liturgical and festival changes, and fearful of the interference of an increasingly Polish-orientated sovereign into the affairs of the Grand Duchy. Mialecii Smatrycki (1577-1633), for a time hostile to, but later a supporter of the Uniate cause, had been received at the Salamarecki estate at Siomkava, near Minsk, on his return from Leipzig, and was said by Syrakomla to have written a part of his anti-Uniate polemical work Threnos or the Complaint of the Eastern Church during his stay there. When the Union ofBierascie was duly signed in 1596, many of the inhabitants of Minsk accepted it without protest. Those who did not follow the advice of the Vilnia Holy Ghost Confraternity, obtained from the Minsk magistrates in 1613 the grant of land for a church by the Niamiha, and called for non-Uniate priests from Vilnia to service it. The Grand Duke, who resented the establishment of these non-Uniate confraternities which, with their schools and fund-raising activities for Muslim-occupied Constantinople, began to look very much like a hostile state within a state, sent two Uniate Greek-rite priests with royal letters-patent to seize the church building. The fair minded city fathers, however, appear to have been sympathetic to the Minsk confraternity, and received the royal envoys, Luckievic and Hainski, with some coldness, declaring that the city council had many other worries apart from church affairs, and in the event nothing was done. Indeed, the first decade of the 17th century had been a time of sharp famine and plague, as w-ell as of outbreaks of fire in the city (1602), so their claim had some justification The three attempts in August 1616 of the newly established non-Uniate Cathedral confraternity, led by the shoemaker Danila Palavinka, to seize the Holy-Ghost Cathedral, followed by the unlawful detention by the mob of the Catho lie and Uniate burgomasters Alaksiej Filipovi^ and Siamion Chatkievic merely served to strengthen the fears of the peaceful majority of townspeople over the political undertones of the Confraternity's campaign, and to advance the cause of the Greek Catholics.The publication in 1617 ofLavon Kreuza's Oborona Jednosti Cerkovnoj ("Defence of the Union") in reply to Smatrycki's Threnos was a skillful and convincing polemical work, which won over many waverers to the Union.

Since 1596 the bitterest disputes had arisen between the two factions over the ownership of Church property. These resulted in two outbreaks of unrest in Minsk (1597, 1616), and the martyrdom of the Uniate Archbishop of Polacak Josaphat Kuncevic (1580-1623); they were finally settled at a conciliation meeting between the contending parties, held in Minsk in 1625. Both the Uniate Metropolitan Jazep Veniamin Rutski and the non-Uniate Metropolitan Peter Mohila attended the conference, which took place at a time when the Muscovite rulers, weakened by internal strife, driven back from Novgorod and Smalensk, and at odds with the Cossacks, were no longer in a position to interfere in the affairs of the Grand Duchy.Another Uniate School of SS. Cosmo and Damian opened in 1619. At this time also were built the Dominican monastery (1622), the Bernhardine convents (1628, 1642), and the Basilian Church of the Holy Ghost (1645), all in the Upper Town, as well as the Basilian convent of the Holy Trinity in Trinity suburb (1630). A privilege was also granted by the Grand Duke Ulad^islau I (Pol. IV.) in 1633 to the Basilian convent of the Holy Ghost and to the Orthodox Confraternity of SS. Peter and Paul, to establish printing presses; in the same year the increasingly wealthy Confraternity founded a Hospital and a School "for the instruction of Christians and their children". By the mid-17th century the non-Uniates of Minsk had seven Confraternities owning houses, shops and land; the majority of city churches and their endowments however remained in the hands of the Greek Catholics, secure from the Turkish Sultan and the Russian Tsar.

Thereafter Minsk enjoyed several decades of prosperity during which trade flourished. A number of Merchant corporations were established after 1552 - the Guild of Metalworkers (1591), the Jewellers (1592), the Merchant Taylors (1592), the Shoemakers (1609), the Sad-diers (1622), the Barbers (1635), and the Skinners (1647) Other guilds included the Tile-makers, Hatters, Cooks, Carpenters and Furriers. Churches, town houses and public places were embellished, and culture generally (iconography, music, sculpture and the applied arts) reached high levels of achievement.

The Muscovite Wars and the Polish Ascendancy (1648-1700)

In 1633 a Dutch founderer Witte established a cannon-factory al Tula, the first in the domains of Tsar Alexei Michailovic, thus finally breaking the arms embargo which the Empire, the Hansa and the Grand Duchy had sought to impose on their unruly eastern neighbour. This sounded the death knell of the peaceful interregnum enjoyed by Minsk since 1580. By 1648 the Muscovites had rearmed the Cossacks and in 1652 they were ready to resume hostilities against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Belarus. A host of 700 000 men, (as large as Napoleon's Grande Armee), embarked on a campaign equipped and financed - according to the Syrian eye-witness Paul of Aleppo - by the merchants of Moscow, grown enormously wealthy since the fall of Kazan and Astrakhan (1554, 1556) on "merchandise from Persia and India", and anxious further to enrich themselves by eliminating their Grand Ducal trading competitors between the Baltic and the Black Sea The Moscow Patriarch Nikon added his widow's mite of 20.000 armed men, recruited from among his monastic servants, to join in the expedition. Smalensk fell after a short siege in 1654; Nicholas Radzivil and his captains were held prisoners in Kazan. The Belarusan fortress cities of Viciebsk, Mahilou, Polacak and Orsa on the Dniapro were also taken in swift succession.

The account of the fall of Minsk among other cities, and the manner of the legendary "reunion of Belarus with the Russian state" by Tsar Alexis, is best left to the contemporary Orthodox Deacon Paul ofAleppo, then in Moscow (1653-1655): "His various officers subdued upwards of ninety four towns and castles, by storm and voluntary surrender; killing God only knows how many Jews, Armenians and Poles, and throwing their children packed in barrels into the great River Dnieper without mercy; for nothing can exceed the hatred which the Muscovites bear to all classes of heretics and infidels. All the men without exception they cut to pieces, not sparing one: the women and children they carried into slavery, after destroying their habitations so as to leave their town entirely desolate. Thus the country of the Poles, which formerly was pro-verbially rich, and bore comparison with the finest provinces of Greece, now became a vast scene of ruin, where not a village or inhabitant was to be found in fifteen days journey in length and breadth. We were informed that more than one hundred thousand of the enemy were reduced to captivity, so that seven or eight boys and girls were sold for a dinar or less; and many of them we ourselves saw. In the towns which they took by capitulation, they spared all those inhabitants and allowed them to remain, who embraced the faith and were baptised: the rest were all expelled. But the towns which they captured at the point of the sword they totally cleared of their inhabitants, and levelled their houses and fortifications to the ground." Other sources set the toll of ruined cities and towns in Belarus between 1654 and 1656 at over two hundred.

Minsk on 30th June 1.655 "readily surrendered to the Orthodox Tsar", and two Muscovite Princes, Arseniev and Chvorostin, were appointed as governors. The inhabitants were given the choice of "accepting Russian Orthodoxy (pravoslavyje) or of being removed from the city by order of the Tsar" The manner of their 'removal', whether by chain-gang or by river as described by Paul ofAleppo, needs no further elaboration. Subsequent exactions and ill-treatment of the population, however, moved the remaining Orthodox citizens to rebellion after two years, which was swiftly dealt with by the Muscovites. By 1660 how-ever, the tide of war had changed. The Russian forces were overstretched and in 1661 Jan Casimir regained Horadnia and Vilnia after long sieges. The Cossack Ataman Zaiatarenko was killed before Stary Bychou, and Minsk was retaken. The citizenry of Mahilou rose up to massacre the Muscovites, dispatching their leaders in chains to Warsaw. Recovery from the holocaust was slow, and only got under way in the latter part of the 18th century. "The glorious city of Polacak" which, according to Vakar, "once had 100.000 inhabitants, and was larger and wealthier than London," had "only 360 frame houses, inhabited by 437 Christians and 478 Jews in 1780". In the latter stages of the war the fortunes of the Commonwealth improved, and Minsk again became an advanced camp for the liberation of Belarus by the Grand Duke Jan Kasimir (1648-1668) who, together with the future sovereign Jan Sobieski, visited the ruined and plague-ridden city of Minsk on no fewer than three occasions in 1664.

Peace was restored by the Treaty of Andrussovo in 1667. Its terms, however, ultimately proved to be the death warrant of Belarus as an independant state, for it contained a clause giving Moscow the right to intervene on behalf of the small Orthodox minority in the Grand Duchy and Poland, a right confirmed in 1686, and repeatedly and oppressively invoked by succeeding Russian ambassadors almost yearly thereafter. However, another three decades of peace ensured for Minsk a period of reconstruction and growing prosperity, with an increase in brick and stone-built houses, and in the embellishment of new churches. The convent of the Franciscans was restored in 1673 by the city Stolnik (High Steward), Todar Vankovii. In 1679 the privileges of the Jews of Minsk were confirmed by the King and Grand Duke Jan Kazimier. The Calvin-ist chapel was also rebuilt in 1671, thanks to a gift of timber from Janu§ Radzivil, and the minister Krystaf z Zarnauca, was relieved from hold-ing his services in the open air. By 1680 however, his office had to be conducted with some circumspection, on occasion in a private house, to avoid molestation from rowdy pupils from the Jesuit school. Established in Minsk since 1654, that Order was richly endowed by benefactors af-ter 1667, in particular by the Vajavod of Troki, Cypryjan Brzastouski, whose family remained patrons of the Jesuit college for many years. Other benefactors included Stanislas Zablocki, Jan Filipovic and Jury Furs, who contributed gifts for the building of the new Church from 1701-1705. A Benedictine convent was later established in vul. Zbarovaja (Internacyjanalnaja W.) in 1700 by Anna Steckievic, widow of the Banneret of Minsk, and a Carmelite house was founded in the Rakouski suburb by Todar Vankovic in 1703. In addition to the Church of the Holy Ghost on Cathedral squate, the Uniates had at the end of the 18th century three other churches in the Lower market, at the southern end of the Tatar suburb and by the southern fortifications of the city, near the site later occupied by the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Jubilejny Dom BNR.

Fearful of further Russian claims on the Grand Duchy, official policy sought to integrate the Belarusan population into the Polish sphere by downgrading their institutions, including the Uniate Church, and smoothing out the differences between the Polish language and its Belarusan 'dialects'. In 1697 all official documents were required to be written not in the Cyrillic, but in the Latin script - lacinka. Even in some Uniate service books, prayers and hymns in Polish were intro-duced, often disguised in the old Slavonic script, the better to gain ac-ceptance and promote the 'unification' of the Commonwealth. The policy was to some extent understandable in the face of continuing Russian encroachments, the more so because even ethnographers of Belarusan descent such as A. Rypinski, were unclear as to the true place of the Belarusan people between the Western and Eastern Slavs. Its effect however was dire for the future of the Belarusan language and culture.

The Decline and Partitions (1700-1795)

During the debilitating Northern wars (1700-1721) between the Commonwealth, Sweden and Russia, Minsk was twice occupied by the armies of Peter the Great, and once by Charles XII. During his first visitation in 1704, Peter dined twice very civilly with the Jesuits and inspected his troops in the Upper Market; characterisically, however, during his second stay in 1708, his Cossacks and Kalmuks plundered the city, sparing neither Catholic nor Orthodox churches, and set it on fire.

With the return of peace, there was an improvement of communi-cations. Roads and Canals were built: postal services were set up in Belarus in 1717 between Vilnia, Minsk and Mahilou, and between Minsk and Navahradak. The Dominicans established a school in 1727, and in 1752 a Pan §y§ka founded a church of St. Roch in vul. Kojdanauskaja (Revalucyjnaja) More Guilds were formed by Royal privilege in 1744 for the protection of local trade: - the Vintners, the Gardeners, the Wa-ter-carriers, the Brewers and Meadmakers. Occasionally conflicts of ju-risdictions between the Municipal Courts, the Grand Ducal Court, the Church Courts and the Seignorial Courts-Leet in matters of breach of trade monopolies and unfair competition. Against a background of dy-nastic squabbles between the increasingly polonised Bykouskis, ZaviSas and Valadkovi^y, rivalries between the various religious orders (includ-ing a famous street-fight in 1728 between the Dominicans and the Jesu-its over some runaway schoolboys), processions, parades, street fairs with dancing bears and firework displays, the Grand Ducal era of Minsk teetered to its close. The city's great Va/avodand benefactor Ihnat ZaviSa (whose portrait with the sitter, wearing the aristocratic sash or pojas, is to be seen in the National Museum of Art), died in 1739, and was laid to rest after a solemn Requiem at the Maryjnski Cathedral in a blaze of over 4.000 candles and 12.000 votive lights.

Periodic conflagrations (1737. 1764 and 1778), famines and out-breaks of the plague led to some reconstruction of Churches and houses in brick rather than wood, and also to the foundation of more hospitals. The great fire of 1737 resulted in the rebuilding of the two Bernhardine convents in the Upper Town (including the present Holy Ghost Cathe-dral), yet another outbreak in 1764 occasioned the rebuilding the Uniate Holy Trinity convent in Traecki pradmicscie. A conflagration in 1778 finally destroyed the old timber-frame castle within the earthworks by the Niamiha. An ever-increasing number of houses in the city were be-ing built out of brick, many of which have survived, and in this respect Minsk was well in advance of Russian cities such as Moscow. By the mid-18lh century Minsk had two benevolent hospitals. As for schools, in addition to fee-paying pupils, the Jesuit college admitted as scholars the children of poor families free of charge, until the suppression of the Order in 1773. Both the Basilians and the Dominican monasteries offered similar free educational facilities, and by 1771 there was also a Mariavitan school for girls in Trinity suburb.

Meanwhile the election of each new sovereign " Augustus II (1697-1733), Augustus III (1733-1763) and Stanislas Poniatowski (1764-1795) - and the escalating complaints of the non-Uniate Greek-rite minority, gave a pretext for foreign intervention. In 1733 Minsk was occupied by more than 20.000 Russian soldiers, cavalry and infantry under General Volkonsky, accompanied by the inevitable swarms of Cossacks and Kalmuks, though it is said that in the event they were on their best behaviour. Inevitably perhaps in these unsettled times, the Grand Duchy was plagued by bandits such as Adam Kroner whose raids sowed panic throughout Belarus, until his capture and execution in 1737.

Ultimately the Commonwealth was dismembered by Russia, Prussia and Austria in three partitions. Polacak, Viciebsk and Mahilou were annexed by Russia in 1773. A judicial re-organisation of the Grand Ducal Courts followed, resulting in the removal of the Sessions of the High Court from Minsk to Horadnia in 1775, but in 1791 the city became the seat of the Court of Appeal for the Vajavodstvy (Counties) of Polacak, Viciebsk and Minsk. Two years later in 1793, the city and the bulk of the remaining Belarusan part of the Grand Duchy were occupied by the Russians. A successful attempt had been made by the government of the Commonwealth to persuade the non-Uniate faction in Belarus to leave the Russian jurisdiction for that of Constantinople. Although the Belarusan Orthodox had agreed to the reform, the Russian Empress Catherine would not hear of it, and seized on the move as a pretext to intervene definitively and entend her domains further to the west. By 1796 the whole ethnic territory of Belarus had been absorbed in the Russian Empire, of which it was to remain a part for almost 120 years.

Minsk under Russian Rule (1795-1917)

The Russian Governors' first step was to restrict the Belarusan Greek-Catholic Church, the Basilian Convents in the Upper Town and in Trinity suburb were closed in 1795, and the Holy Ghost Church handed over to the Russian Orthodox hierarchy, who in 1796 renamed it after the apostles SS. Peter and Paul. The former Belarusan Orthodox church of that name on the Niamiha was re-consacrated to St. Catherine, thus commemorating the patrons of the two sovereigns who had established Russian rule over the city Plans were then drawn up for improving the city's amenities, public gardens were laid out by the river Svisiac, which were named the Go vcrnor 's Gardens, and the architect Todar Kramer was commissioned to remodel the City Guildhall, the Vice-governors residence (1800), the Basilian monastery, how a school for children of the gentry (1799), the Merchants' Exchange (1800), the Jesuit college and the Holy Trinity convent in the Trinity suburb (1799) and other buildings. These reconstructions were done to neutral neo-classical designs of West European municipal architecture, which left little room for national particularism.

In 1812 the French Emperor Napoleon crossed the Nioman river, making the purpose of his campaign against the Tsar plain to his generals. Irritated, after a meeting with Alexander's envoy. General Balachov, by the pretensions of successive Russian Tsars to make themselves the arbiters of European politics, he exclaimed to his generals Berthier, Caulaincourt and Duroc: "Alexander takes me for a fool. Does he think I have come to Vilnia to negotiate trade agreements? I have come to finish off, once and for all, this colossus of the barbarians of the North. The sword is drawn. They must be driven back to their ice-fields, so that for twenty five years they don't come meddling in the affairs of civilised Europe...He [Alexander is afraid and wants a settlement, but I will only sign a peace treaty in Moscow... If he wants victories, let him beat the Persians, but let him not meddle with Europe. Civilisation repudiates these Norsemen. Europe must put its house in order without them." The composition of his confederate army - French, Poles, Italians, Germans, Dutchmen, Portuguese and Austrians - gave some weight to his claim to be acting for Europe. Napoleon, leaving Marshal Oudinot to hold Polacak, and Marshal Davout to occupy Minsk, drove on to Viciebsk Only some 180.000 men set off from Smalensk for Moscow: the rest were protecting the Grandc Anncc 's flanks or were on garrison duty. Most of whatever material destruction look place during the campaign was caused by the brutal but very effective Russian tactics of "scorched earth" - burning cities (among them Mahilou and Smalensk), villages and crops to prevent them being taken by the enemies of the Orthodox Tsar.

In Minsk Davout received strong local support, and attended a Te Deum celebrated by Bishop Dederko to mark the liberation of the city from Russian rule. A popular move was the decree confiscating the harvests of the fleeing Russian nobility, and dividing them equally between the Army, the Civil administration and the peasants. Implementing Napoleon's plan to restore the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Belarus as two separate states, with their capital in Vilnia and Mahilou, Minsk was made the Prefecture of a revolutionary departement, and numerous Belarusan volunteers formed units in the (Jrande Armce. During Napoleon)

Icons retreat from Moscow, these volunteers fought with great valour, defending the bridges and covering the French crossings of the Biarazina. Allowing for the heavy losses sustained at Borodino and other engagements at Krasnaje, together with subsequent desertions of disaffected Germans and other allies, the arrival at the bridges of 70.000 men in combat order was hardly that of a defeated army. In the words of an old French soldier of the Imperial Guards who made it back to Vilnia: "We gave them a good trouncing at every turn, just the same. Those 'Russkis' are only a bunch of schoolboys." On the return of Kutuzov to Minsk in late November, there were few reprisals, with the exception of Bishop Dederka who was suspended, and a general amnesty was subsequently proclaimed.

Russian rule thereafter remained relatively mild, save for the suppression of the Greek-Catholic Church, until the Uprisings of 1831 and 1863. Then russification began in earnest, with Russian style churches being built in prominent positions, or existing churches being revamped in a sometimes grotesque pseudo-Russian style (SS. Peter and Paulprior to 1979). The national Uniate Church was suppressed in 1839, occasionally at sword point, with numerous recalcitant priests being imprisoned or deported for up to thirty years. Many of the Latin clergy were expelled; the Berhardin convent and Church were given over to Russian Orthodox monks. The Dominican Church became an army warehouse, and the Berhardine Church of St Joseph a city archive. Streets were given different names in Russian to efface the memory of the old order: vul. Franciskanskaja became Gubernatorskaja, Dominikanskaja was renamed Petrapaiilauskaja, Bernhardinski zavulak - Monastyrski, Felicijanskaja - Bogodelnaja, Mastovskaja - Paliciejskaja and so on. An ukazeofTsai Nicholas I. in 1840 abolished the very use of the names Belaruc and Belarusans. The consequences of Kastus Kalinouski's uprising in 1863 were important and far reaching for the city of Minsk, and the surrounding areas. Many thousands of their inhabitants were deported to Siberia, or imprisoned - among them the poet Vikency Dunin-Marcinkievifi, - in the Piiialauski Fortress, erected in 1825, almost in anticipation of future trouble.

Yet apart from these upheavals, a long period of peace brought with it material prosperity. Industry and the arts flourished, though occasional fires and epidemics continued to plague the city. There were two particularly virulent outbreaks of typhus in 1848 and 1853. The Tsars showed little interest in Minsk and seldom visited it, except on tours of inspection to the imperial army headquarters in Mahilou. Alexander I came in 1819 to address the nobility, and Alexander II vis-

Minsk, 1870

ited the city in 1859. Permission to build Catholic churches was generally limited to cemetery chapels, though exuberant Russian Churches and shrines such as the new Cathedral, the Church of the Protection and the Holy Cross, St.Mary Magdalene, St. Alexander Nevski, the Church of the Transfiguration, Our Lady of Kazan and others mushroomed across the city. The old coat-of-arms granted by Zyhimunt IV charged with the image of the Theotokos, which in 1796 had been augmented by the Russian double-headed eagle, was ultimately replaced in 1878 by a field "or, three wavy bars azure ". Perhaps more relevant to the quality of life of the inhabitants was the installation of the municipal water system (1874), a telephone service (1890), two horse-drawn tram-lines (1892) and current electricity (1895).

However, all these attempts to suppress the language, the national symbolica, and to adulterate the visible signs of Belarusan individuality, finally brought growing numbers of Belarusians to the realisation that they were indeed a different nation. Ethnographical tradition engendered national pride, even as the nationalist poets Maxim Bahdanovii and Zmitrok Biadula were born, one of an eminent Minsk ethnogra-pher, the other of a traditionally minded Hassidic Jew from the Lahojsk

hills.The unique flavour of Belarusan life was succinctly captured in works of one of Minsk's greatest residents, who now lies buried here, -Jakub Kolas. During this period Minsk acquired its National Theatre (1890), its first School of Art founded by Ja. Kruher (1906), the beginnings of its "Academy of Sciences" at the Belarusan Chata (1913) and proposals were also made in 1913 for the establishment of a National University in Minsk. Renewed stirrings of national protest came with the anti-Tsarist riots in 1905. There were strikes and demonstrations in Minsk, and the students at the Orthodox Seminary set fire to their college; as a result societies and clubs were dissolved, students expelled and the poets Jakub Kolas, Kastus Kahaniec and Ales Harun, among many others, were imprisoned for their clandestine activities.

Towards Independence (1917-1991)

Later came the First World War and one of the most dramatic episodes in the city's history - the power-struggle between the Belarusian National Rada and the Bolsheviks from 1917-1919. On the national side stood such distinguished patriots as Professor E. Karski, General K. Alexejeuski, Anton Luckievic, Edvard Vajnilovic, the poet Ales Harun, Col. Kastus Jezavitau, Janka Kupala, Jazep Varonka, Count Skirmunt, Zmitrok Biadula, Princess Mahdalena Radzivil (the Countess Markievicz of BelaruS) and others, in particular the railway workers. The Bolshevik side were led by Russian internationalists and professional revolutionaries - Lander, Knorin and Miasnikian,.- backed by mutinous but well armed Tsarist soldiers, who ultimately prevailed. Over the next twenty years, however, the bold ideals of the socialist revolution became stained with the blood of tens of thousands of victims, summarily shot by Bolshevik irezvyiajniki (Special units) in the 'killing-fields' of Golden Hill and Kurapaty. Many more starved to death in rural areas as a result of collectivisation of agricultural land, hastily introduced by the 9th All-Belarusan Soviet Congress held in Minsk (1929).

The arrival of the Germans in 1941, after the encirclement near Minsk by General von Bock of 300.000 Red Army soldiers with more than 300 tanks, brought more bloodshed, with the Nazi mass-murders. However, many Jews escaping death at the hands of the Nazis were sheltered and helped by the local populace. There followed more executions and mass-deportations by the Bolsheviks of so-called "collaborators". Yet some good came from all these ills: Eastern and Western Belarus (formerly under Poland) were reunited in 1939. The Belarusan Repub-

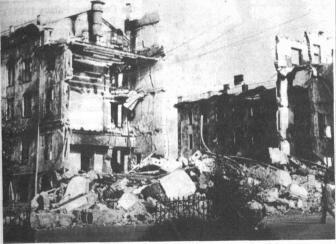

This is what Minsk was like after World War II (1944).

lie was admitted as a founder member of the United Nations in 1946. The ruined city of Minsk was rebuilt as the show-place capital of a modern Republic, larger and more populous than Bulgaria, Denmark, Portugal or Hungary.

The awakening to nationhood in 1863 and 1904, the role played by the citizens of Minsk of every class in the creation of an independent Republic in 1918, and the subsequent destiny of the city as the cultural capital of Belarus, rather than of some administrative area in a Marxist dreamworld, - all this cemented by years of strife, suffering and persecution during the Revolution and the Nazi-Soviet conflict (1941-1945), has helped to make Minsk a united city with a character very much of its own. Despite the destruction and thoughtlessness of planners, a great deal of the old Minsk has survived, and is being painstakingly restored. Neither were the visions of the totalitarian idealists entirely fruitless, as the fine avenues, squares, parks and impressive public buildings of the new Minsk demonstrate. These were the result of plans drawn up as long ago as 1926, which included the constructivist art deco of Government House (1934), the National Opera and Ballet (1939) and the Academy of Sciences (c.1935) by. Ja. Langbard, and later in 1944 with the

Memorial at the territory of Khatyn- one of the dozens of Belarusan villages burnt by fascists together with the residents during World War II.

impressive neo-classicism of the Congress Palace (1954), the Polytechnical Institute (1946), Victory Square (1954) and Skaryna Avenue. Industry, technology and the arts have made great strides, and the city now boasts two airports and a fine modern underground railway system. It has become an international city on the circuit of world statesmen.

But perhaps the greatest moments of Minsk have been in the recent past, when mass rallies in Independence Square, at the Kupala monument, in the City Sports Stadium and at Kurapaty, showed to. the world that the 'forgotten people' had at last become a nation, with thecrowds taking the historic cry of the old peasant at the All-Belarusan Congress in 1917, as the elderly General Alexiejeuski, - a boy at the time of Kalinouski's Uprising (1863), - kissed the white-red-white flag: "Long live free Belarus! Long live the national flag!" Both old and new Minsk have their history and their achievements, which are there for citizen and visitor to enjoy. What has, like Dublin, become known as the Kaohany Horad'("The dear old Town") on a Golden Hill, a city of icons resplendant with gold, in which filigree gates of gold are created out of something as commonplace, yet as rich as plaited straw, and where all the children seem to have golden hair, is surely a fitting capital for the land which poets have called "Belarus, golden Belarus".